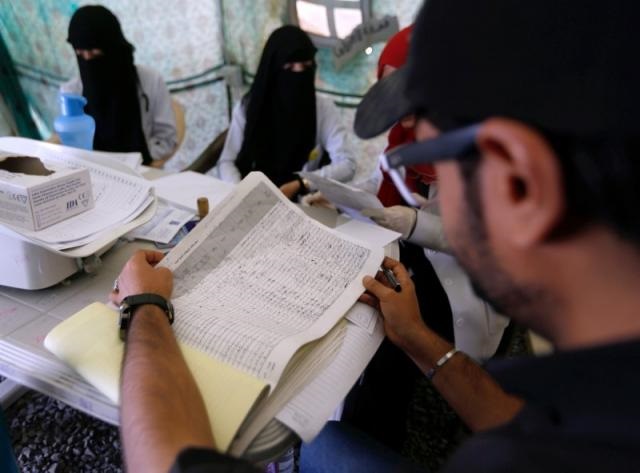

(Reuters) – Yemen’s cholera epidemic has reached one million suspected cases, the International Committee of the Red Cross said on Thursday, with war leaving more than 80 percent of the population short of food, fuel, clean water and access to healthcare.

Yemen, one of the Arab world’s poorest countries, is embroiled in a proxy war between the Houthi armed movement, allied with Iran, and a U.S.-backed military coalition headed by Saudi Arabia.

The United Nations says Yemen is suffering the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, and eight million people are on the brink of famine.

The cholera figure is almost certainly exaggerated, but that does not diminish the scale and complexity of the humanitarian crisis, said Marc Poncin, Yemen emergency coordinator for aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières.

Cholera flared up in April and spread rapidly, killing 2,227 people. The death rate has fallen dramatically, and without laboratory confirmation, recent cases are probably diarrhea, Poncin said.

A new wave of cholera is expected in March or April.

“It’s probably unavoidable. We need to be ready to face another big epidemic,” said Poncin, adding that cholera may become a long-term burden as it has in Haiti.

“The places where the war is active are the ones most at risk for increase of disease.”

The latest emergency is diphtheria, a disease not seen in Yemen for 25 years, which has affected 312 people and killed 35.

It has not spread explosively, as cholera did, but diphtheria outbreaks can affect many thousands, and there is a global shortage of diphtheria anti-toxin. Yemen has enough for 200-500 patients, Poncin said.

An urgent diphtheria vaccination campaign early in 2018 will complicate the WHO’s hope of doing mass cholera vaccination at the same time, especially given the problems with security and accessing remote areas, Poncin said.

The Houthis, who control much of the country, are also suspicious of vaccination drives, he added.

Yemen’s troubles have been aggravated by the Saudi-led coalition’s blockade of its ports, which has caused a fuel shortage and a spike in food prices. The health system has virtually collapsed, with health workers unpaid for a year, although the WHO gives incentive payments for cholera work.

The ports were closed in retaliation for a missile fired from Yemen by the Houthis. On Wednesday, despite a fresh missile attack on Riyadh, Saudi Arabia said it would allow the Houthi-controled port of Hodeidah, vital for aid, to stay open for a month.

Recent Comments